Forests and Trees: the Formal Semantics of Collective Categorization (ROCKY) is an ERC Advanced Grant project that is carried out at the Utrecht Institute of Linguistics OTS. This project aims to develop a novel theory on the linguistic ability to conceptualize collections, applied to a wide range of empirical phenomena and interdisciplinary challenges in computational semantics and comparative linguistics, benefiting from the recent synergy between linguistics and the psychology of concepts.

General description: Languages have various ways of referring to collections like families, herds and forests. The grammatical properties of such collective expressions critically determine how we understand them. For instance, the sentences “this forest is old” and “these trees are old” categorize an arboreal collection using a concept (“old”), while conveying different meanings. This semantic difference correlates with the difference in grammatical number between the sentences: singular vs. plural. Such effects of collective categorization in language are crucial for understanding the connections between grammar and the mind, as well as for artificial intelligence. However, currently little is known about the mechanisms underlying our linguistic ability to conceptualize collections. This project aims to develop a novel linguistic theory of this ability, applied to a wide range of empirical phenomena. This theory will be further implemented for addressing interdisciplinary challenges in computational semantics and comparative linguistics, benefiting from the recent synergy between linguistics and the psychology of concepts (Hampton and Winter 2017). The idea is that when classifying a collection, speakers rely on two inferential principles that operate on mental concepts: (i) geometric inferences: a forest is considered “far away” if all of its trees are far; (ii) symmetric inferences: two trees are “similar” if each of them is similar to the other. The leading hypothesis is that uniform interactions between these inferential principles and the grammar of collective expressions account for collective categorization in language. This hypothesis is explored in three work packages, each of which develops the semantic theory and evaluates it on a different interdisciplinary domain: human interaction with geographic information systems, behavioral linguistic experiments, and comparative linguistics.

Examples

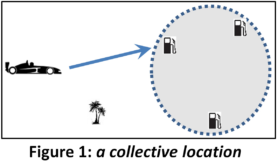

Example 1 – a car race in the desert: Dan is participating in a car race in the desert. Suddenly, he notices that his car is running out of gas. In this context, we consider the following two sentences:

1) a. Dan is far from a gas station.

b. Dan is close to a gas station.

In a pilot study, Grimm et al. (2014) discovered a difference in the interpretation of (1a) and (1b): sentence (1a) preferably pertains to Dan’s distance from all gas stations, a fact which may have fatal consequences for Dan’s trip. By contrast, (1b) only requires Dan to be close to one gas station.

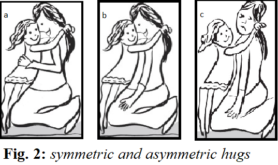

Example 2 – asymmetric hugs: In a truth-value judgment task, Kruitwagen et al. (2017) asked 48 Dutch speakers to consider the Dutch parallel to sentence (2), in the situations of Figure 2.

(2) The girl and the woman are hugging.

Expectedly, most participants judged sentence (2) true in Fig.2a, whereas few judged it true in Fig.2c (100% and 19%, respectively). However, surprisingly, 48% of the participants judged (2) true in Fig.2b, although they considered the sentence “the woman is hugging the girl” to be false in the same situation. This test showed that symmetry is typical of sentences (2) but is not necessary.

Upshot: In both examples, we see speakers categorizing collections – of gas stations, of people – based on properties of individuals: location, actions or intentions. This behavior is quite general. The main research question of the project is: what principles underlie this behavior, and how can they be generalized and used in theoretical linguistics, computational linguistics and experimental linguistics?